To mark the 300th anniversary of ‘Capability’ Brown and in celebration of England’s many fabulous gardens, landscapes and events, VisitEngland is promoting ‘Year of the English Garden‘ as a key PR theme for 2016.

The English are famous the world over for their love of gardens and gardening. From stately homes with vast acres of exquisitely landscaped lakes and parkland to the smallest cottage garden, we take pride in creating something of beauty, somewhere for the kids to play, a place for growing fruit and vegetables – in fact, something that becomes a source of perpetual pleasure.

A garden seldom remains static, but is ever-changing as different tastes develop over the centuries and each age finds its own preferences in style and design. Plants go in and out of fashion; what was ‘absolutely the latest thing’ soon becomes outdated as yet another fad takes hold. Dahlias, for example, were until recently regarded as too garish and old-fashioned for the modern garden; they are now back in favour once more with trendy garden designers.

The earliest gardens in England that we know about were planted by the Romans in the first century AD, and there are still examples that can be seen today. In the Middle Ages, castles, manors and monasteries usually had gardens featuring vegetables and fruits as well as flowers. These gardens were the main method of providing food; herbs were also grown for medicinal and culinary use. Grass was used as a flowery mead, filled with wild flowers.

Tudor gardens are famous for their knot gardens. Box, often used today, was not popular. Instead, scented herbs such as marjoram or thyme were used. Knot gardens, deigned to be seen from above, featured intricate patterns replicating the threads in a piece of needlework; they often featured symbols or puzzles. The centres were normally filled with gravel, or occasionally with flowers or herbs, making the hedges the main feature. Arbours were popular, covered with climbers such as honeysuckle or jasmine. Lilies, sweet William and roses were grown for their scent.

Under the Stuarts, garden design became more formal, following the influence of the French and the Dutch. Gardens became more symmetrical; the Tudor knot gardens were replaced by elaborate parterres. Topiary became popular, trimmed into formal shapes, symbolising man’s domination over nature.

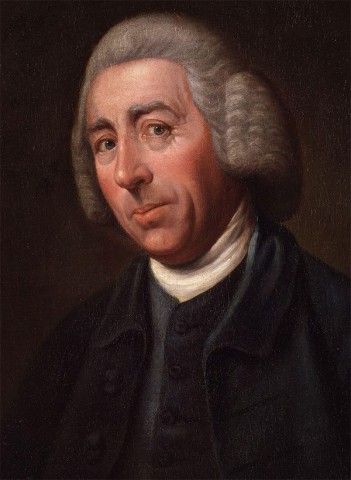

We are all familiar with the style of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716 – 83) whose nickname derived from his habit of informing his clients that their gardens had ‘great capabilities’. He advocated a more natural style, with flowing lines of landscape, lakes and trees, uninterrupted by hedges or fences, so that the house seemed a part of the surrounding countryside.

Tastes changed again in the Victorian period. The preference was for massed beds of colourful flowers laid out in complex patterns. Many public parks and gardens were created, with the intention of ‘bringing culture to the masses’.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the influence of Gertrude Jekyll changed the public taste once again. She had a painter’s sense of colour and line, and was strongly influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement. She believed a garden should reveal unexpected views and pleasing surprises. Under her influence, herbaceous borders became immensely popular, as did the concept of planting in colour schemes. Other, more modern, garden designers, such as Christopher Lloyd, introduced bold planting schemes with colours that clash as well as harmonise.

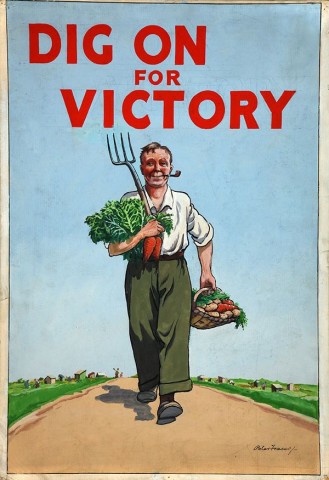

Gardens changed yet again during WWII; there was a danger that a sea blockade could starve out the British people, as imported food was vulnerable to attack. So the Dig for Victory campaign was introduced, encouraging people to transform gardens and parks into allotments. People also kept chickens, pigs, rabbits and goats.

‘Dig! Dig! Dig! And your muscles will grow big. Keep on pushing the spade! Don’t mind the worms, just ignore their squirms. And when your back aches laugh for glee, just keep on digging till we give our foes a wigging. Dig! Dig! Dig! for Victory!’

Through all the centuries, the humble cottage garden, with its exuberant mix of traditional flowers, a kaleidoscope of colour and texture interspersed with vegetables planted will-nilly among them, has never lost its place in the hearts of English gardeners. Favourite plants are hollyhocks, delphiniums, aquilegias, clematis and roses.

Today many modern gardens tend to be much more self-consciously ‘designed’ with striking arrangements of hard landscaping, unusual features and minimalist planting.

The English passion for planning, planting, propagating and pruning remains as strong as ever and shows no sign of abating… now, where did I put those secateurs?

Jill Sidders | NWR Sittingbourne

Enter our two new competitions that are inspired by the Year of the English Garden 2016:

Main cover image credit: Sudeley Castle Queens Garden sited on the original Tudor parterre, with high hedges and a formal planting pattern and paths. VisitEngland/Sudeley Castle