In perfect weather on Wednesday morning, members of Bury St Edmunds group met at Suffolk Wildlife Trust’s ‘Black Bourn Valley’ nature reserve, mainly to enjoy a good walk, but also to see and discover how ‘wilding’ and ‘rewilding’ can affect a former farming landscape. It is a very interesting subject to look at more closely.

Our walk was followed by a lovely lunch at a nearby pub – the perfect combination!

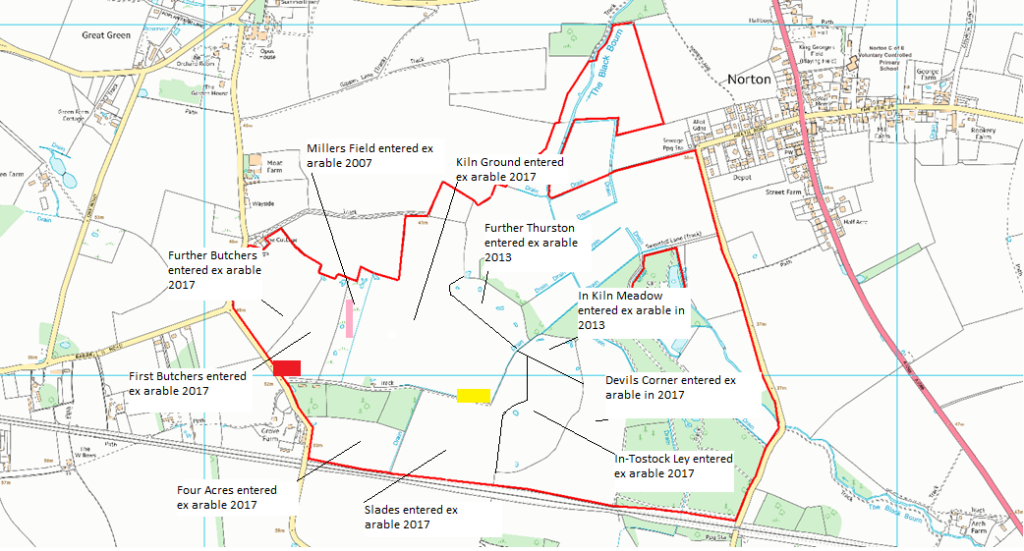

Grove Farm was generously gifted to the Suffolk Wildlife Trust in 1995 and is gradually being transformed into the Black Bourn Valley Nature Reserve by taking fields out of arable farming and allowing nature to take over. This is not ‘rewilding’ in the truest sense of the word – since that would indicate reverting land back to something it once was, and historical baselines are but sketchy at best as to what things were really like. Instead, this is ‘managed wilding – making it wilder from this point forward.

The first small field was experimentally left in 2007 to see what would happen. This now contains thickets of hawthorn, blackthorn and dog rose, habitat for resident and migrant birds, along with ponds attracting dragonflies, damselflies and great crested newts. In the open grassy patches, pyramidal and common spotted orchid have sprung up of their own accord, as well as plants such as common centaury.

Other field parcels have gradually entered ‘ex-arable’, and in 2017 arable farming ceased altogether. Currently, free roaming cattle access the whole reserve, grazing the grassland, knocking against the scrub, and scraping/scuffing the ground, all of which helps create habitat diversity, including feeding grounds for turtle doves. Fields left to revert are now dominated by plants such as bristly oxtongue and thistle which attract yellowhammer, linnet and goldfinch, while skylark can be seen hovering above the open fields. The old scrub may look ‘scruffy’ but is a perfect home not only to resident birds all year but also breeding summer migrants such as nightingale and turtle dove.

In the wet meadows, two shallow seasonally wet scrapes have been formed, which fill with water through winter into spring and dry out in summer so that what was essentially an empty field now attracts lapwing, redshank, snipe, shoveller, teal, gadwall, wigeon, little and great white egret, marsh harrier, the odd pintail and heron. It has become a real haven for wildfowl and waders.

Changes on the reserve are continually monitored, but the benefits of giving nature more space are clear. Former arable fields can become rich in wildlife when nature is allowed to take the lead. Such an approach could help reverse wildlife declines across intensively farmed landscapes.